The information revolution we are going through today brought upon societies an almost unbearable weight of realization on how easily the truth can be distorted with small or big lies.

It may have started with the rise of personal social media profiles that made even a very average person doubt about what they watch or read. At least about that one particular Facebook or Instagram friend next door they surely know is living a crappy life yet is showing so cool and valuable on his or her profile pictures.

What does Galileo have to do with all of this? Well, Galileo’s case is a perfect example of how parts of the truth were bent and distorted throughout time. How finally, several hundred years later, a new and more accurate narrative of Galileo’s life events can be shared worldwide (thanks to the information revolution of course).

And how is that? Pretty simple. Before the internet and the option to have endless amounts of data shared for free around the world, the course of history was written by pretty much only selected ‘few’. Opinions were voiced and multiplied by some other selected ‘few’ again. To print books was pretty expensive, and their reach was limited, leaving many people relying on the spoken word and hear-say opinions.

With the introduction of the paper press, radio, and TV, ironically information was even more censored and biased. That’s why having only limited sources of information and having only limited ways to spread information made our pre-internet school textbooks (and even some university ones) sometimes quite limited in explaining what is to be thought of as historical fact.

So, who was Galileo Galilei, and what is he most famous for? If you google his name the first link you will see is Wikipedia article that names him the ‘father of observational astronomy’, the ‘father of modern physics’, the ‘father of scientific method’ and probably the most common, the ‘father of modern science’.

A pretty impressive list for one person, right? But, was he really such a genius, or was his life story taken hostage in order to spread some other ideas and misconceptions?

Hopefully, we’ll find it out just by looking closer at a few terms from Wikipedia cited above, or by even just taking a look at the origin of his most famous quote ‘And yet it moves’ (in original Latin ‘Eppur si muove’).

FATHER OF MODERN SCIENCE

If Galileo was the ‘father of modern science’, who were the grandfathers then? This question brings us right to the middle of the issue with Galileo being claimed so importantly for modern science.

Readers need to be aware that Galileo himself did not make a ‘quantum leap’ in scientific methods that would bring our understanding of natural sciences to some other level.

A level that would be too far advanced compared to the science knowledge before Galileo. There were many philosophers and teachers around Europe for centuries, thinking in empirical terms and debating movements of Earth before Galileo actually got in trouble with the Church Inquisition. So, who are those grandfathers?

Let’s start from the beginning. Charles Homer Haskins, a history professor at Harvard University and an American historian of the Middle ages said that ‘Universities are, just like cathedrals and parliaments, a product of the Middle Ages’.

This needs to sink into every reader: Universities, as we know them in western civilization, are products of the Middle Ages.

The first university was started in Bologna (North Italy) in 1088, followed by Paris (1150), Oxford (1167), Palencia (1208), and Cambridge (1209). Before the end of the 14th century, another 24 universities were established around Europe. In the 15th century, there were 28 more. Most of them were funded and organized by the Catholic Church and local men of power (kings, independent city councils, or high nobility). Note that the first formal split within Western Christianity happened only with Henry VIII of England and he lived in the 16th century.

So, the Catholic Church and men of that time actually started to organize a systematic approach to world knowledge (not just by studying wisdom, nor ideas or theories - but also applying empirical methods while observing nature). There was another very important thing about early universities - they were all allowed to be autonomous. Thoughts and research could be done independently of any pressure from the outside. Of course, over the centuries such pressure at the times seemed overwhelming, but the general idea of the autonomy of the universities was never neglected.

And it was amazing how back then when means of travel were so scarce, many of the scientists and lecturers knew of each other, exchanged knowledge (because all of them spoke and wrote in Latin), and travelled frequently around Europe visiting or lecturing on different universities.

Let’s get back to the grandfathers. I shall mention a few that are critical for understanding how scientific thought (centuries before Galileo) evolved from a pure repetition of known wisdom to applying an empirical method as a way to make a conclusion based on observation.

GRANDFATHERS OF MODERN SCIENCE

Robert Grosseteste (12th/13th century) was an Oxford student, teacher at Paris University, and later rector of Oxford University.

Grosseteste played a key role in the development of the scientific method. He introduced to the Latin West the notion of controlled experiment and related it to demonstrative science, as one among many ways of arriving at such knowledge. Although not always following his own notions, his work is seen as instrumental in the history of development of the Western scientific tradition. Among the Scholastics, Grosseteste was the first to fully understand Aristotle's vision of the dual path of scientific reasoning: generalizing from particular observations into a universal law, and then back again from universal laws to the prediction of particulars. Grosseteste called this "resolution and composition". So, for example, looking at the particulars of the moon, it is possible to arrive at universal laws about nature.

But, apart from that, Grosseteste also introduced the idea of the subordination of the sciences where math is the highest of all sciences, and the basis for all others, since every natural science ultimately depended on mathematics.

Albertus Magnus (13th century) studied at the University of Padua, lectured on many German universities, and finally became a theology professor at the University of Paris. Thomas Aquinas (another great scholastic) was his student.

Albert was known for his huge writing opus. His writings were collected in 38 volumes. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of topics such as logic, theology, botany, geography, astronomy, astrology, mineralogy, alchemy, zoology, physiology, phrenology, justice, law and others. Most modern knowledge of Aristotle was preserved and presented by Albert.

Albert's knowledge of natural science was considerable and for the age remarkably accurate.Not only did he produce commentaries and paraphrases of the entire Aristotelian corpus, including his scientific works, but Albert also added to and improved upon them. His books on topics like botany, zoology, and minerals included information from ancient sources, but also results of his own empirical investigations.

These investigations pushed several of the special sciences forward, beyond the reliance on classical texts. Albert also effectively invented the entire special sciences, where Aristotle has not covered a topic. For example, prior to Albert, there was no systematic study of minerals. For the breadth of these achievements, he was bestowed with the name Doctor Universalis.

From Wikipedia:

Much of Albert's empirical contributions to the natural sciences have been superseded, but his general approach to science may be surprisingly modern. For example, in De Mineralibus (Book II, Tractate ii, Ch. 1) Albert claims, "For it is the task of natural science not simply to accept what we are told but to inquire into the causes of natural things.

Roger Bacon (13th century) studied at Oxford and years later became a lecturer at the same University. He also went to teach at the University of Paris, but after a couple of years in Paris spent the rest of his life focused on research and writing. Known as one of the earliest European advocates of the modern scientific method.

From Wikipedia:

Medieval European philosophy often relied on appeals to the authority of Church Fathers such as St Augustine, and on works by Plato and Aristotle only known at second hand or through (sometimes highly inaccurate) Latin translations. By the 13th century, new works and better versions – in Arabic or in new Latin translations from Arabic – began to trickle north from Muslim Spain.

In Roger Bacon's writings, he upholds Aristotle's calls for the collection of facts before deducing scientific truths, against the practices of his contemporaries, arguing that "thence cometh quiet to the mind". Bacon also called for reform with regard to theology. He argued that, rather than training to debate minor philosophical distinctions, theologians should focus their attention primarily on the Bible itself, learning the languages of its original sources thoroughly.

He was fluent in several of these languages and was able to note and bemoan several corruptions of scripture, and of the works of the Greek philosophers that had been mistranslated or misinterpreted by scholars working in Latin. He also argued for the education of theologians in science ("natural philosophy") and its addition to the medieval curriculum.

William of Ockham (13th/14th century) studied at Oxford and later spent many years at different universities in continental Europe. Most famously known for Occam’s Razor or the law of parsimony which is the problem-solving principle that "entities should not be multiplied without necessity."

From Wikipedia:

William of Ockham espoused fideism, stating that "only faith gives us access to theological truths. The ways of God are not open to reason, for God has freely chosen to create a world and establish a way of salvation within it apart from any necessary laws that human logic or rationality can uncover."

He believed that science was a matter of discovery and saw God as the only ontological necessity. His importance is as a theologian with a strongly developed interest in a logical method, and whose approach was critical rather than system building.

Nicole Oresme (14th century) studied at Paris where he later became a professor. Like other scholars of the Middle Ages, he also wrote many influential works covering very different science fields: economics, mathematics, physics, astronomy, philosophy, but he also covered astrology and theology that was back then considered as part of overall natural science.

From Wikipedia:

In his Livre du Ciel et du monde Oresme discussed a range of evidence for and against the daily rotation of the Earth on its axis. From astronomical considerations, he maintained that if the Earth were moving and not the celestial spheres, all the movements that we see in the heavens that are computed by the astronomers would appear exactly the same as if the spheres were rotating around the Earth.

He rejected the physical argument that if the Earth were moving the air would be left behind causing a great wind from east to west. In his view, the Earth, Water, and Air would all share the same motion. As to the scriptural passage that speaks of the motion of the Sun, he concludes that "this passage conforms to the customary usage of popular speech" and is not to be taken literally.

He also noted that it would be more economical for the small Earth to rotate on its axis than the immense sphere of the stars. Nonetheless, he concluded that none of these arguments were conclusive and "everyone maintains, and I think myself, that the heavens do move and not the Earth.

Nicholas of Cusa (15th century) studied at the University of Padua and is considered to be one of the first German proponents of Renaissance humanism.

From Wikipedia:

The astronomical views of the cardinal are scattered through his philosophical treatises. They evince complete independence of traditional doctrines, though they are based on the symbolism of numbers, on combinations of letters, and on abstract speculations rather than observation. The earth is a star like other stars, is not the center of the universe, is not at rest, nor are its poles fixed. The celestial bodies are not strictly spherical, nor are their orbits circular. The difference between theory and appearance is explained by relative motion. Had Copernicus been aware of these assertions he would probably have been encouraged by them to publish his own monumental work.

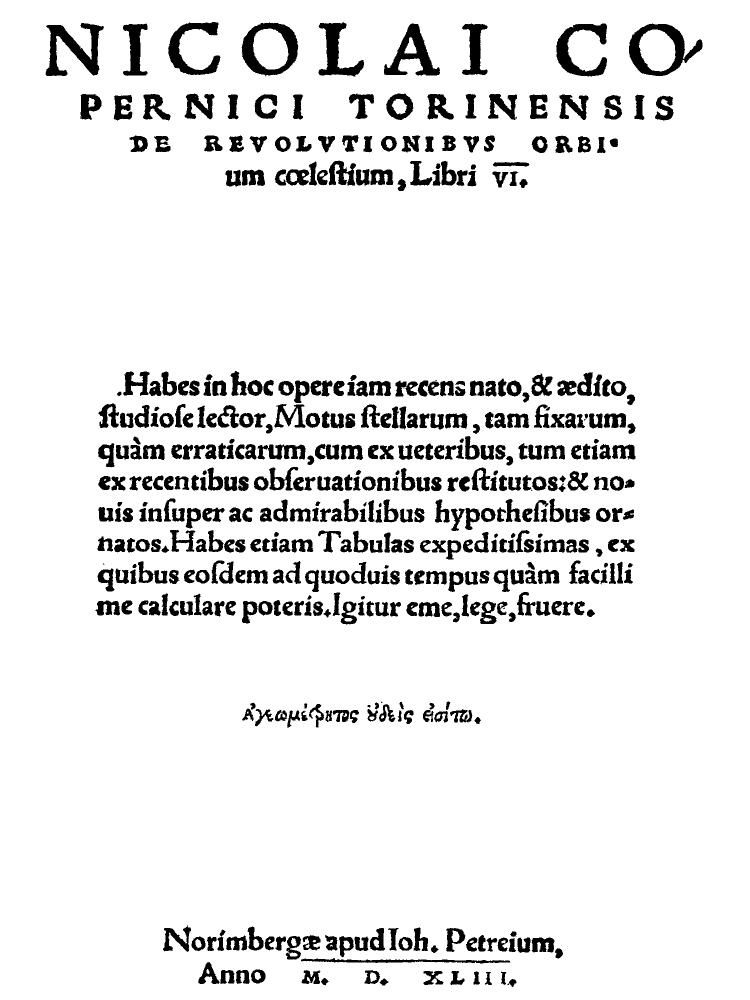

Nicolaus Copernicus (15th/16th century) studied at the University of Bologna, Padua, and Ferrara where he gained wide humanistic knowledge of that time. He obtained a doctorate in canon law and was also a mathematician, astronomer, physician, classics scholar, translator, governor, diplomat, and economist.

The release of his book "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium" (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) is considered as a major event in the history of science, triggering the so-called Copernican revolution that led to another popular term: the Scientific Revolution.

And what was so revolutionary about this book? First of all, Copernicus was the first one who explicitly put the Sun in the center of the solar system. And Earth was just one of the planets that were circling around it. It is considered that he came up with such a conclusion independently of ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician Aristarchus of Samos. The other great moment was that Copernicus described all those movements using math and geometry.

Aristarchus put forth a theory of the Sun and not the Earth being the fixed center of the universe.But, unfortunately, everything in that book, apart from the fact that the Sun is the center of the Solar system, was wrong. His mathematical and geometrical explanation of the movement of the stars and planets was based on the assumption that all of them move in circles which is not true. Therefore, his mathematical calculation of positions of the objects in the sky could not be accurate (he also proposed a new calendar).

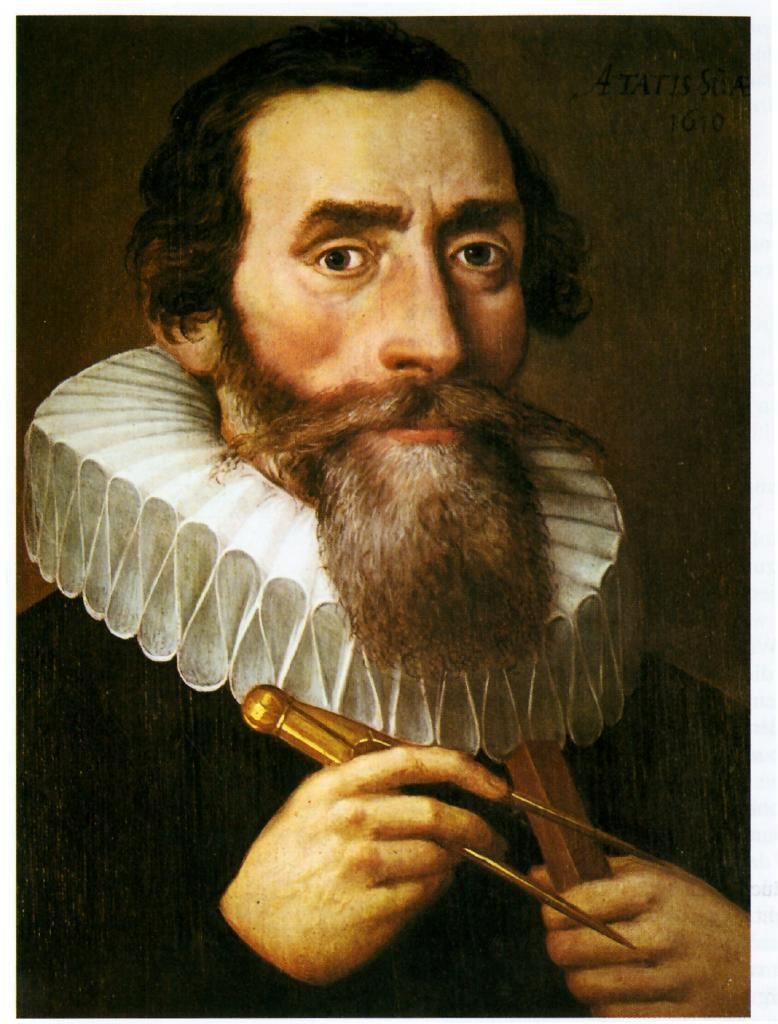

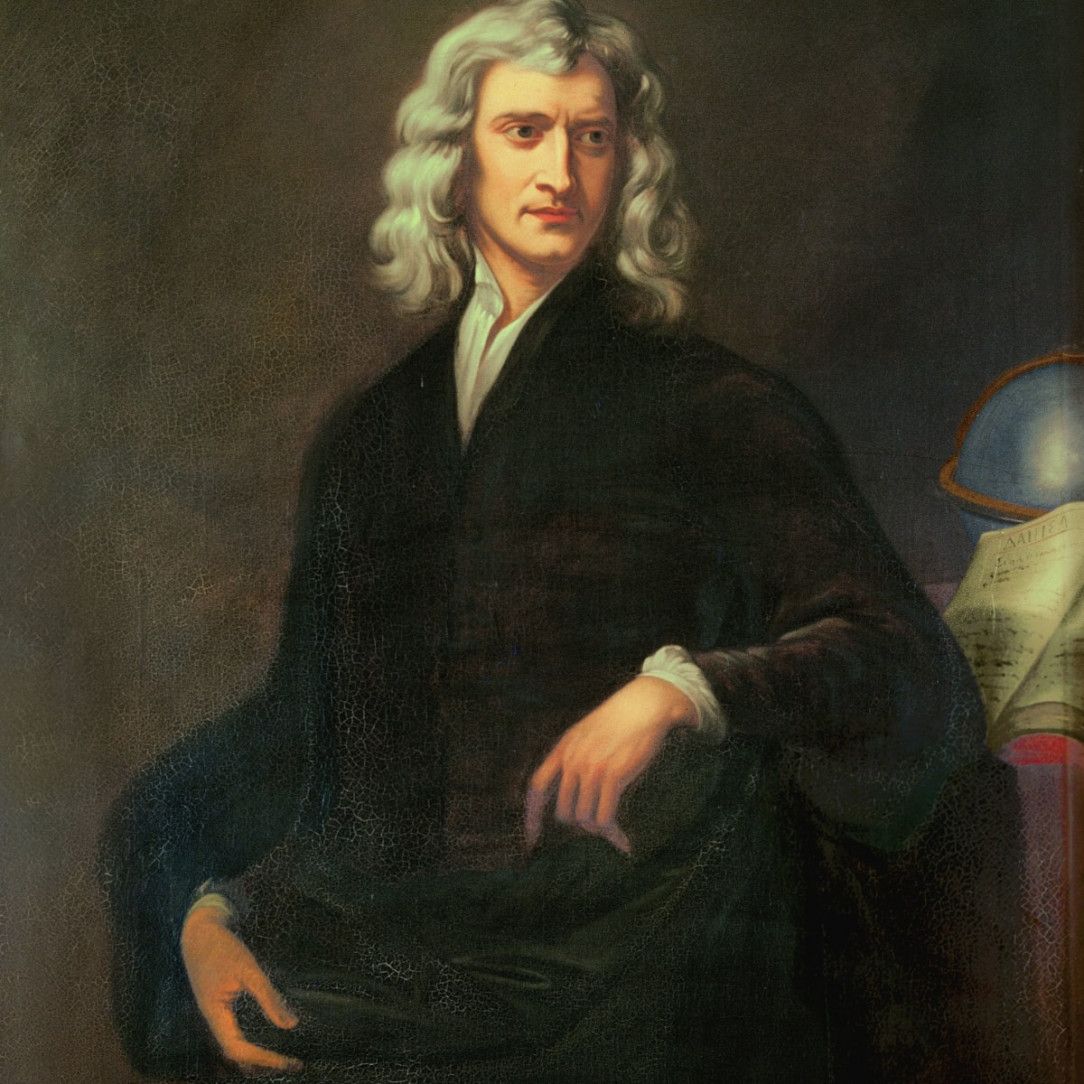

Only when Johannes Kepler (16th/17th century) introduced the elliptical movement of the objects in the sky, things fell in place. But even Kepler did not know how to explain why planets and stars are bound to always follow the same orbit. That was again figured out only later by Isaac Newton (17th/18th century).

All in all, just by looking at these few mentioned scientists over the course of some 500 years before Galileo, it is more than clear that the birth of ‘modern science’ did not happen in one generation or with just one brilliant mind.

BACK TO GALILEO’S WORK

Let’s go back to the first half of the 17th century, to look at the life and work of one person that would in the coming centuries be considered a pivotal player of modern science. And, what is a more common understanding today, a determining argument that the Catholic Church (which is still active today with some 1.2 billion members) goes against modern science. Or, at least, can’t keep up with its development.

At the time Galileo lived there was already a heavy burden of division between Protestantism and Catholicism weighing down from northern parts of Europe. There was also a 30years war on the go that brought more division and wrath among European societies (it is estimated that some 8 million people died, out of which 20% were German).

What's also important is that a Catholic counter-reformation was in full swing. Due to all of this, Catholic Church began to closely watch what was published and discussed among its own members (and that of course included Universities and their lecturers).

But nevertheless, popes and their leading clerics did not want to put pressure on scholars and were actually actively looking for a way to protect scholars and their works from getting into a conflict with the Church teaching. Many scholars (among them many were clerics) were discussing different geocentric and heliocentric systems already and were trying to find proof that would determine which system was right.

Unfortunately, Galileo was not able to prove his support of heliocentrism (and so couldn’t anyone at that time) but was unlike others far more into insisting he was right on the matter.

In 1615 (a year before Copernican doctrine was banned by the Church and Galileo was ordered for the first time to abandon it as an objective fact, and ONLY research it as a mathematical model in astronomy – which he agreed to do), one of the most prominent cardinals of that time (also one of the Doctors of the Church), Robert Bellarmine, wrote a letter to another heliocentric, called Paolo Antonio Foscarini:

I say that if there were a true demonstration that the sun is at the center of the world and the earth in the third heaven, and that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun, then one would have to proceed with great care in explaining the Scriptures that appear contrary, and say rather that we do not understand them, than that what is demonstrated is false.

But I will not believe that there is such a demonstration until it is shown to me. Nor is it the same to demonstrate that by supposing the sun to be at the center and the earth in heaven one can save the appearances, and demonstrate that in truth the sun is at the center and the earth in heaven; for I believe the first demonstration may be available, but I have very great doubts about the second, and in case of doubt one must not abandon the Holy Scripture as interpreted by the Holy Fathers.

This means nothing else than the fact Church cannot recognize theories that are yet to be proven, and until that happens, it will be guided by the Holy Scripture (the Bible is supporting geocentric view of the universe in few places) and the teachings of the Fathers of the Church (prominent theologians, but also decisive authorities when it comes to understanding natural science up to that point).

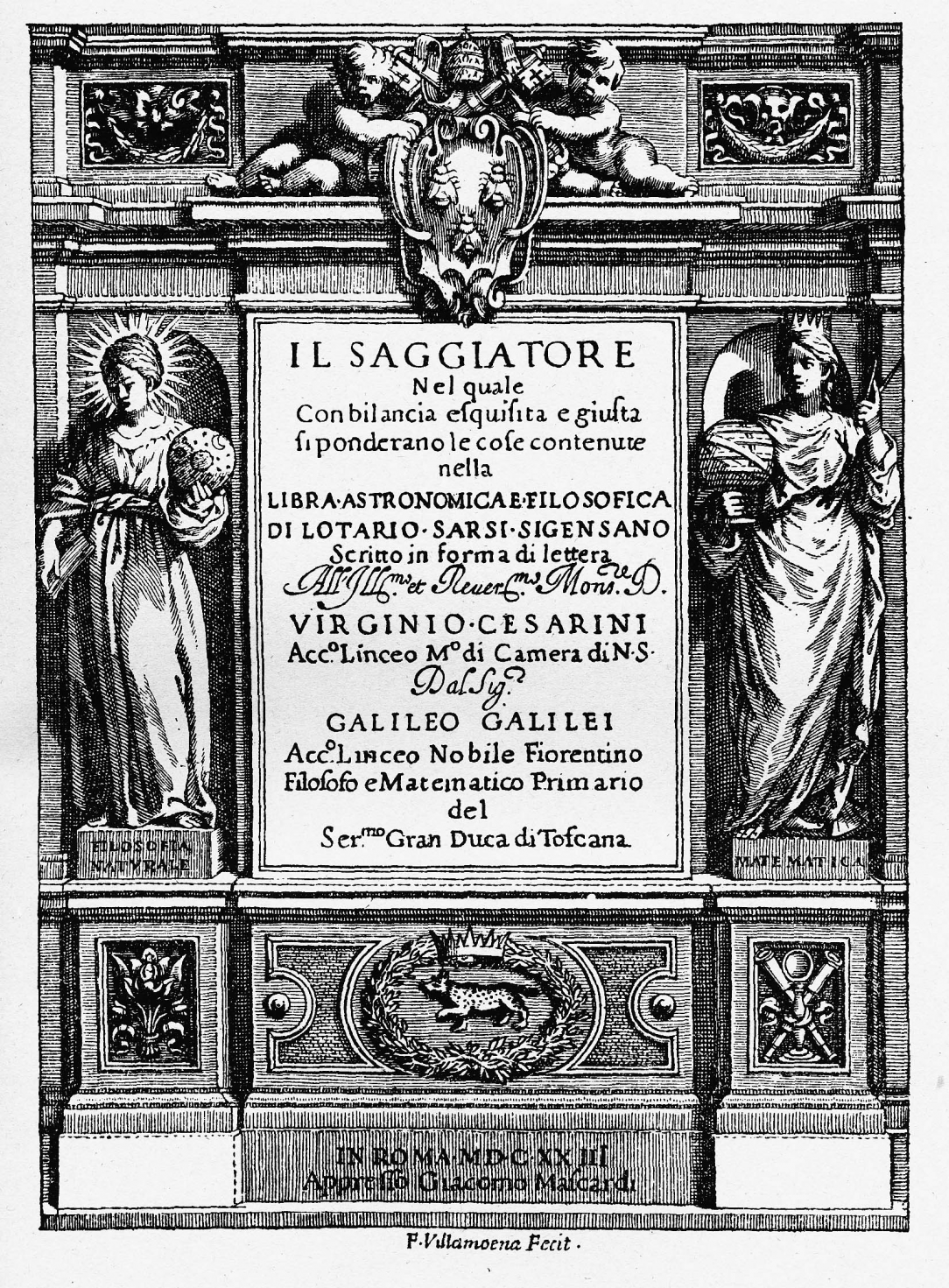

During those intense years Galileo’s work ‘The Assayer’ was published in Rome in 1623. It is considered one of the pioneering works of the scientific method, but also it was written to oppose Jesuit mathematician Orazio Grassi.

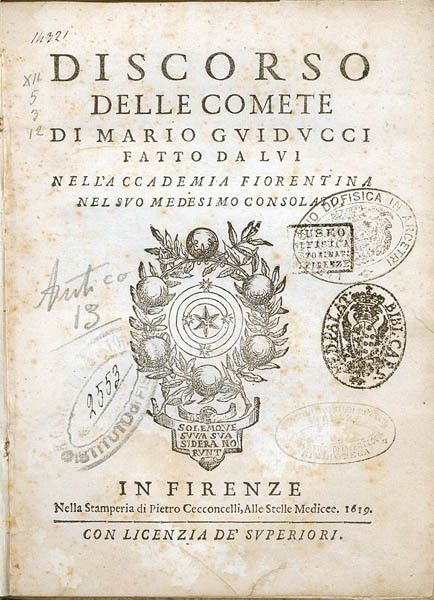

Galileo writes here that science can be discovered and explained only by math, but he also disputed Grassi using some quite arrogant words, claiming (without any proof again) that comets are not celestial bodies, but rather an optical illusion.

Another important detail around this book is that it was dedicated to the pope – Urban VIII (previously a cardinal, a member of the Barberini family). Urban was Galileo’s longtime supporter (even before he became the pope in 1623) and the book had Urban’s family crest on its cover, which can only mean Galileo was fond of this person or owed gratitude for the support he received during the years. So, it looked like everything was good between the two of them. Prominent scientist Galileo Galilei and the most important person in Italy, Urban VIII, seemed to be on the same side.

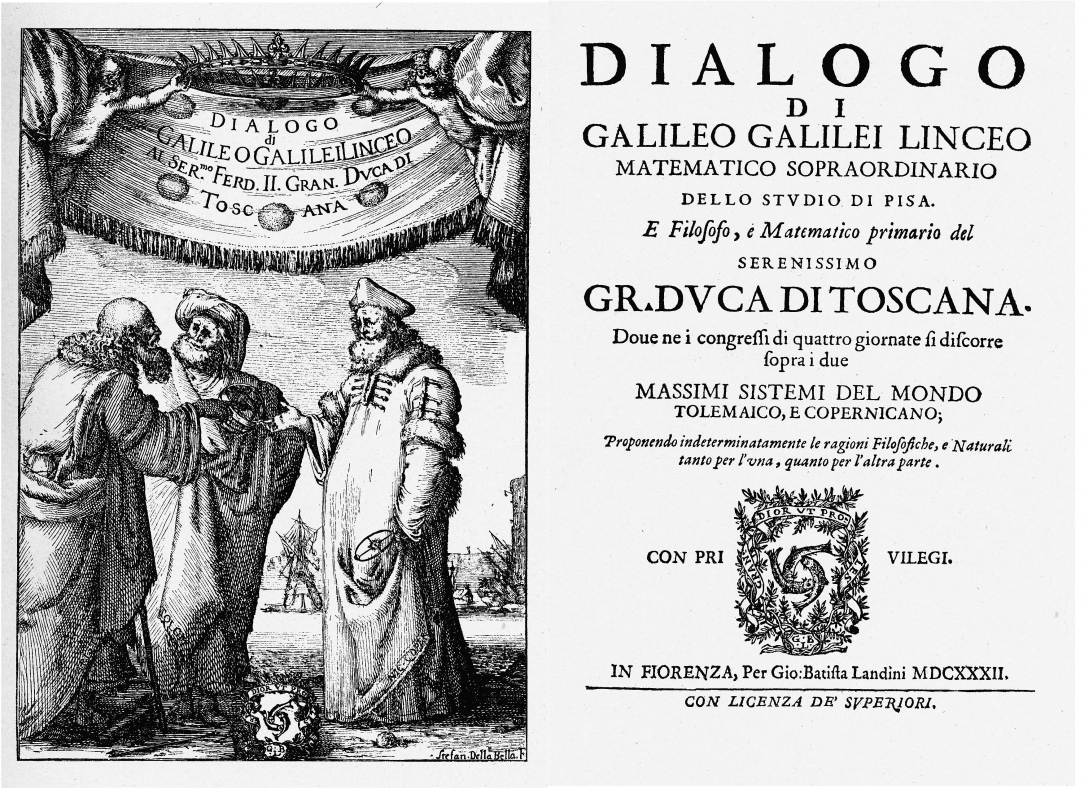

But, some 10 years later Galileo came up with the new book Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems which was at first approved both by pope Urban and the Inquisition. The Pope asked Galileo (for the sake of political correctness) not to advocate heliocentrism in that book, but to rather show both systems without weighing in on one side. Galileo accepted the remark but used quite the wrong approach (at least that’s how it ended up) to show his opinion on Aristotle’s geocentric view.

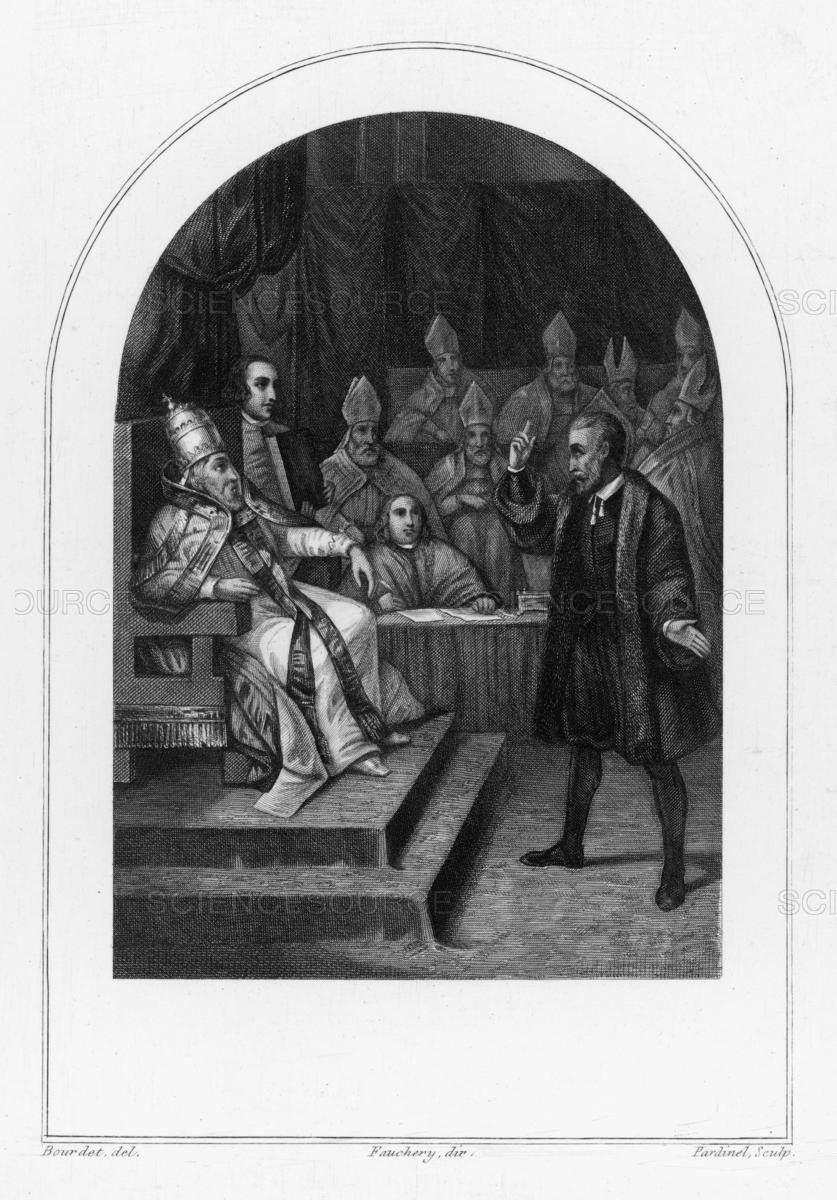

In this book, a person who was defending current Church teaching at that time was named Simplicio and his geocentric arguments were often debunked in a way Simplicio turned out to be a fool. Simplicio in Latin/Italian also had a connotation of a simple person. And that was it. The pope got insulted and the clash of two egos went to another level, where the pope had much more power. The Inquisition was called in. And that’s how Galileo got in trouble.

Not because he ‘invented’ heliocentrism, not because he proved it and the Church did not want to accept the proof. It was actually quite opposite – Galileo could not prove heliocentrism but insisted it was correct. And called everyone else a fool for not accepting his thoughts.

To make it clear - that was not the only scientific theory Galileo insisted on but could not prove. He also insisted that the movement of the Earth was responsible for shifts in ocean tides. And he was stubborn about it the same way as he was stubborn with the heliocentric theory. The only reason why that topic was never brought up is simply because it had no impact on the Holy Scripture writings and therefore was not in clash with Church teachings.

The trial ended fairly quickly, and the sentence of the Inquisition was delivered on 22 June 1633. It was in three essential parts (from Wikipedia):

Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy" (though he was never formally charged with heresy, relieving him of facing corporal punishment), namely of having held the opinions that the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves, and that one may hold and defend an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. He was required to "abjure, curse and detest" those opinions.

He was sentenced to formal imprisonment at the pleasure of the Inquisition. On the following day, this was commuted to house arrest, under which he remained for the rest of his life.

His offending Dialogue was banned; and in an action not announced at the trial, the publication of any of his works was forbidden, including any he might write in the future.

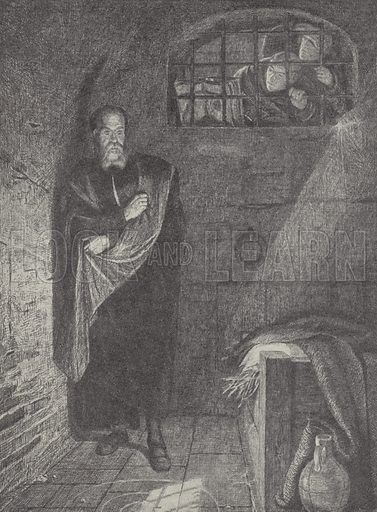

So, the rest of the life (9 years) Galileo spent in his own house (not in some prison without any means to keep up with his work) but under house arrest. However, he was allowed to take visits and there were many, all the way until the year he died. During those remaining years he wrote another book, ‘Two new sciences’ out of which two modern scientific fields arose: kinematics and strength of materials.

And this was the book that got him named ‘father of modern physics’. He died at the age of 77 and was at first buried in a modest grave (due to his status of a condemned person), but later in 1737 was buried in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence where a monument was erected in his honor.

EPPUR SI MUOVE

‘And yet it moves’ is an epic sentence Galileo apparently spoke after he gave up his teachings in front of the Inquisition (referring once more to a heliocentric theory that Earth moves around the Sun). This one short thought, apparently whispered when he was walking away from the courtroom, would make him an anti-Church superhero who, even after being sentenced and condemned, persisted in his own views and went against the false, but powerful authorities.

Over the centuries this sentence, as well as a whole Galileo’s life story were amplified so much, they became one of the iconic arguments against the validity of the Catholic Church and its teachings (on the same level of disgust as the Crusades or the Inquisition are still considered to be).

But that same famous sentence ‘Eppur si muove’ actually showed up in the literature only 100 years after Galileo’s death. The only ‘real proof’ of its existence can be found in one painting that apparently belongs to Galileo’s era, but as far as it can be confirmed, that same painting was created only in the 19th century. And, although it exists, it is not available for the public or historians to determine its real origin.

All in all, not everything was so straightforward between stakeholders that determined Galileo’s life. No doubt he pioneered new concepts and methods and deserves to be considered one of the geniuses of western science, but there are many other great scientists and scholars that paved the road to Galileo’s time.

And there were many more colossal scientists after Galileo that actually were able to prove aspects of heliocentrism. Like Johannes Kepler (who moved the focus from circular movements of the planets to elliptical movements, which were finally able to be explained with math calculations). Or Isaac Newton who is most famous for explaining gravity and its impact on the universe (which resolved one more challenge of understanding the universe). Even a stellar parallax, a key proof of heliocentrism, was conducted only in 1838 by Friedrich Bessel, some 200 years after Galileo’s theory was condemned.

Common False stories about Galileo

A lot of misinformation is going around about Galileo. Let's debunk them.

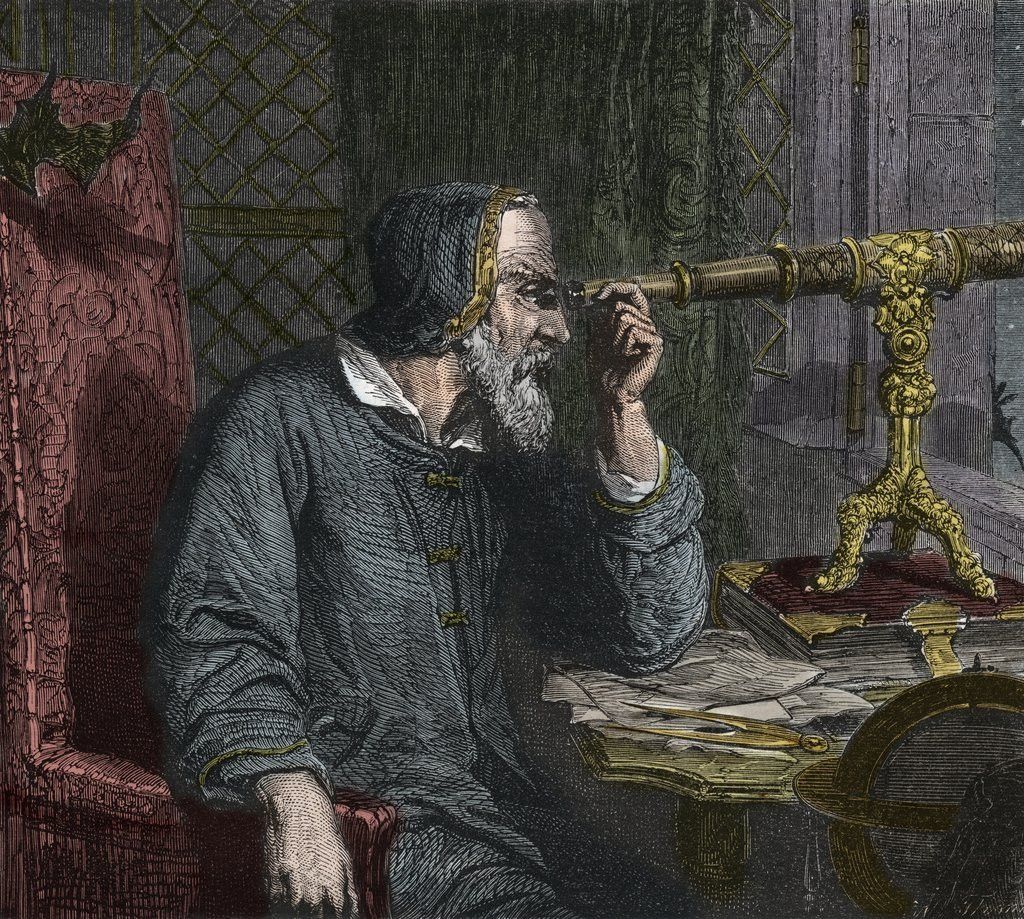

Myth: Galileo Invented the telescope

Fact: The first telescope was patented in the Netherlands in 1608 by Hans Lippershey.

Fact: However, when Galileo heard about the telescope and how it’s made, he created one on his own and made it a bit more precise. He is also credited as the first person in the history who turned his telescope towards the sky and recorded some very precise movements of Venus as well described Sunspots.

Unfortunately, staring at the Sun directly for too long over the years brought him to complete blindness near the end of his life.

Myth: Galileo invented heliocentrism

Fact: It wasn’t Galileo. Formally it was Nicholaus Copernicus. Although at that time there was a vivid debate among the scholars considering various different geocentric and heliocentric models. Apart from the old geocentric model Church supported and Copernicus’ heliocentric model that was pushed by Galileo, there was another one that was proposed by Tycho Brache.

Credit: Galileo tried to explain the heliocentric model mathematically too, but failed because he followed Copernicus’ idea that planets travel around the Sun in circles. However, based on Galileo’s own observation of the stars and planets he himself got convinced into heliocentric accuracy so hard he even faced Church Inquisition and penalty two times.

Myth: The church was (and still is) against science

Fact: Church officials back then were very clear that they would accept heliocentrism if it could be proved. At the time when Galileo lived, it wasn’t and could not be fully proven. Therefore, it was not supported and eventually got condemned, but simply because Galileo tried to push it as a new reality without sufficient evidence.

Credit: Just by reading the words of Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, it is clear as day the whole dispute between Galileo and the Church was completely unnecessary. But unfortunately, official condemnation of later proven theory of course fueled many theories and narratives against the Church and its views about the world all the way up till now.

Myth: Galileo spent his days in a real prison

Fact: Galileo spent all his time (including days of trial) either as a guest of some prominent clerics or later (after condemnation) in his own house in Florence where he was visited by many over the years.

Credit: Although in house arrest, Galileo was allowed to keep up with his work. During those remaining 9 years of his life, he wrote ‘Two new sciences’, probably the most important work that got him to name the ‘father of the modern physics’

Galileo's own false claims

Galileo was wrong in some cases as well:

Myth: Tides are the result of Earth rotation

Fact: Tides are the result of the Moon's gravitational influence on Earth. That was explained properly only after Isaac Newton's discoveries.

Myth: Comets are an optical illusion

Fact: Comets are celestial bodies and were correctly explained by Jesuit scientist Orazio Grassi whom Galileo publicly ridiculed with his own false claim that comets are just an optical illusion.

Myth: Planets move in circles in the heliocentric model

Fact: Planets do not move around the Sun in circular paths but rather in elliptical paths. This was discovered by Kepler.

Myth: The Scripture is wrong about the true relation of the Earth and the Sun, therefore needs to be explained differently.

Fact: Galileo’s position on the Holy Scripture got him in actual trouble with the Church. Since the Church was the only institution allowed to change any teaching, it preserved the exclusive right on how Holy Scripture is to be explained. And Galileo wanted to interfere with it through his own claims about the heliocentric model. As he could not prove it fully, but still went public denouncing the official (Holy Scripture proofed) geocentric system, it all ended up bad for him.

CONCLUSION

Galileo’s case proves how easy it was before the information revolution to manipulate and interpret facts in order to keep the public away from the objective truth. Those facts were abused up to the absurd level of misconception of the events.

Like Voltaire himself did while writing about Galileo’s ‘torture’ in the ‘dungeons’ of the Inquisition, portraying him as a martyr for objectivity. If we fast forward to today, we can hear Stephen Fry or read Sam Harris are bluntly echoing the same false narrative about Galileo being tortured by the Inquisition.

Of course, that inevitably leads to another conclusion that the Church actually wanted to shut down any scientific view of the world. And that is a divisive manipulation that prevents many (a)theists today to take a more sober view on the tremendous sociological, cultural, and of course, the scientific impact the Church and its members, both clerical as regular, had on the western culture during past centuries (or maybe better said, during past millennia).

To me, when it comes to thinking about who is ‘the biggest’ among all of the scientific geniuses, I prefer Isaac Newton’s famous words when he would look back upon his own work - 'If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.'

REFERENCES

Wikipedia- Charles Homer Haskins: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Homer_Haskins

- Robert Grosseteste: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Grosseteste

- Albertus Magnus: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albertus_Magnus

- Roger Bacon: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Bacon

- William of Ockham: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_of_Ockham

- Nicole Oresme: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicole_Oresme

- Nicholaus of Cusa: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_of_Cusa

- Nicolaus Copernicus: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolaus_Copernicus

- Robert Bellarmine: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Bellarmine

- Paolo Antonio Foscarini: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paolo_Antonio_Foscarini

- Johannes Kepler: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Kepler

- Isaac Newton: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Newton

- Friedrich Bessel: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Bessel

- Marilyn Adams, William of Ockham

- Rodney Stark, Bearing False Witness: Debunking Centuries of Anti-Catholic History

- Christopher Bellitto, Introducing Nicholas of Cusa

- Kristopher Kaczor, The Seven Big Myths about The Catholic Church - Distinguishing Facts from Fiction about Catholicism

- James B. Given, Inquisition and Medieval Society: Power, Discipline and Resistance in Languedoc

- Hubert Jedin, Handbuch der Kirchengeschichte